Imposter Syndrome as an Artist, Professional, and Patient

Also known as what I've learned about owning my story and checking my gut as an artist, a professional, and a patient with a not-so-obvious illness.

I've been thinking about Imposter Syndrome more in the last year as I've made transitions in my life, both professionally and personally. December marked 16 years since my diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. It also marked 1 year since I made the leap from full time artist to side-hustle painter. As I've navigated conversations about feelings of inadequacy resulting from those parts of my life, I've come to see the ways in which my diagnosis process influenced my views of my who I am as a patient and as a professional.

If we want to look at this through the lens of a narrative (my favorite), my first introduction to Imposter Syndrome came during my diagnosis process in 2001 at the age of ten. I had just entered sixth grade, and 9/11 had just rocked the United States. While I had symptoms of myasthenia gravis (MG) for many months prior, my symptoms became less intermittent and more severe and persistent during this time. The nurse saw me a lot—so much in fact, the school counselor got involved. While the truth I can put to words now, the fact is that at the time I had no idea how to accurately describe what was happening to my body. My ocular muscles were so weak that the whiteboards were unreadable due to double vision. My hands could barely grip a pencil. I often slurred my words during class. Some days I could barely carry my backpack from my locker to the bus. During lunch, I was unable to chew and swallow. Sometimes I would choke on water or my own saliva. The school counselor suggested to my mom that what I was experiencing was psychosomatic—an emotional response to a tough transition to middle school. Dissatisfied with that assumption, my mom promptly withdrew me from school.

We began the diagnosis process shortly after when my time at home during the day made it apparent to my parents just how physically weak I was becoming. I still faced skepticism and disbelief at this time. After being rushed to the ER for difficulty breathing, my discharge papers included a note from the resident that I was a hysterical young girl, nothing more. A neurologist concluded that low weight was not due to the inability to chew and swallow food, but that I was merely a picky eater and left that appointment with instructions for my mom to cook foods that I liked.

Even after definitive (and might I add rigorous) diagnostic testing, textbook symptoms, and positive blood work led to the correct diagnosis of MG, the skepticism of others left an impression on me. To the untrained eye, I looked just like any other middle schooler. Even close friends assumed that the hell I was experiencing was nothing more than emotional instability or behavioral issues. A neighbor put a pamphlet in our mailbox for a school for "troubled girls". Despite unshakable evidence contrary to this, I still found myself asking...

Am I faking this?

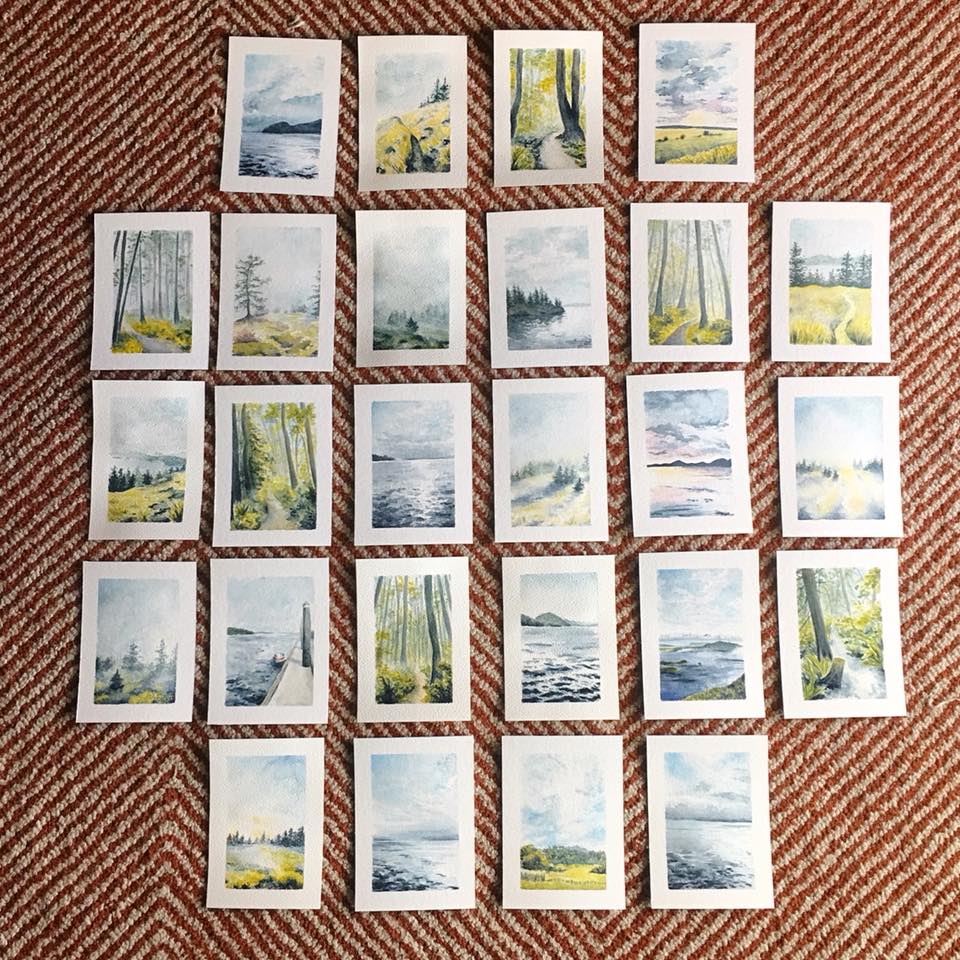

That question bled into other areas of my life for years. I allowed it to produce feelings of inadequacy. I constantly felt like I was "behind" everyone else, and had to work to catch up. I wondered if others questioned the legitimacy of my contributions in class, in projects, and eventually at work. After earning my BA in studio art and eventually pursuing painting as a full time vocation, I still struggled to claim the title of "artist". A co-worker had to recently remind me that after a year of full time as a Community Support Manager, others did in fact trust and value my opinion on matters of community support, crisis management, and conflict resolution.

I'm an artist. I'm a community support manager. I'm an MG patient.These are real and true parts of my life, and I'm not an imposter in any of them.

176917_1671452633983_3212359_o

Cue Stuart Smalley and the need for daily affirmations. So many of us feel like we are faking our way through seasons of life, which is pretty much the definition of Imposter Syndrome. Here's the thing. It's not all bad. I'm a work in progress, but I want to share a few tips that help flip Imposter Syndrome on its head.

It can actually be a good thing to be able to question yourself and your intentions. It helps maintain a healthy perspective, and keep you open minded to new ideas and experiences. Just don't do it too much. Introspection is good and self-deprecation is not.

Don't let healthy skepticism blind you to the very real experiences and truths of those who do life around you. Questions lead to dialogue, which can lead to understanding. As much as you may question yourself, give grace when questioning the intentions and validity of the experiences and opinions of those around you.

On the flip side, know that you don't have to prove your self worth to others who demand it. There will always be people in your life who demand justification that you really don't any obligation to divulge.

You are what you wonder others will perceive you as... I have tried multiple times to retype that in a way that makes it sound less like a riddle. But what I'm saying is this. Call yourself an artist, even if you wonder if others will view you as one. You are one when you embrace that part of your narrative. It's not like a driving test or the bar where you have to legally meet a certain number of requirements to earn a title. Nope. The think you feel like you are faking your way through is still a present part of your reality, and that means you can claim that piece of your life as true and real.

Some days I feel like I am faking my way through all of these things: artist, long-term patient, manager... on a good day I'm all of these things and more. On a bad day, I question if I can claim those titles at all. In the very least, I can keep trying to remember how to make that inclination towards self-doubt help me to be a better version of myself.